The Raspberry Pi Trap

If you spend enough time watching tech YouTube or reading homelab content, you’ve probably noticed the Raspberry Pi comes up a lot.

Want to get started with IT? Grab a Raspberry Pi.

Want to learn server clustering? Grab a few Raspberry Pis.

Want to build a lab around Kubernetes? Obviously, even more Raspberry Pis.

It’s an exaggeration, but look at popular tech channels and you’ll find countless videos for things like Pi-hole or Kubernetes.

At some point, the Pi stopped being a suggestion and became the default answer for new homelabbers.

Not because the Raspberry Pi is bad hardware, but because hardware is a tool and tools have specific jobs. The pi being so prevalent still in 2025 might suggest that you need something special, purpose-built, or trendy before you’re “allowed” to learn real systems.

That mindset kills a lot of curiosity people have far more than any hardware limitation ever could. Once learning feels gated by gear, most people stop trying.

I wanted to push back on that with the least exciting option possible, my almost ten-year-old Mac mini that cost less than a Raspberry Pi.

You Do Not Need a Powerful PC to Start

A lot of homelab advice is either use your old gaming computer, old laptop, or, in some cases, a raspberry pi.

New boards. Mini clusters. Low-power ARM systems. All framed as a good way to begin. The assumption is that learning infrastructure requires new or specialized hardware.

It doesn’t.

My first “homelab” device was this mac mini that an old manager gave me so I could start my lab. No upgrades to be had. No tuning contests. No benchmark screenshots. Just an old x86 box treated like a small server.

The goal was not to see how far I could push it. The goal was to prove that meaningful learning does not require impressive hardware.

What Is Actually Running

This is not a toy setup, but it is intentionally restrained.

- Proxmox as the base hypervisor

- Windows Server 2022 running Active Directory

- A Windows 11 desktop joined to that domain

- A Wazuh VM collecting logs

- An Ubuntu VM running Portainer and FreshRSS

That covers identity, authentication, monitoring, and basic Linux services. These are the exact building blocks people say they want to learn when they ask about homelabs.

There is no Kubernetes. No clustering. No complexity added just to look serious. Everything here exists because it teaches something concrete.

What Matters for Learning

The most important question is not whether this setup is optimal.

It is whether it prevents meaningful learning and experiments.

The domain controller starts and behaves like a domain controller.

The Windows client joins the domain and authenticates.

Logs flow into Wazuh and are readable.

FreshRSS stays responsive.

Nothing needs constant tuning or babysitting.

That matters because when the platform remains just a tool, the focus shifts to the systems themselves. You spend time learning how identity works, how logs behave, and how services interact, instead of fighting the hypervisor that’s hosting the operating systems.

For a learning environment, that’s the win.

There’s Always Tradeoffs

To make everything fit on a single, older box, some compromises were deliberate.

The Windows 11 VM is running below Microsoft’s recommended minimum RAM of 4 GB, sitting instead at 3 GB. The Wazuh VM is also undersized. That would be unacceptable in production but, This is not production.

The Windows desktop exists to learn identity, authentication, and policy. If that’s it, the need for memory goes down. Wazuh exists to show what gets logged, what matters, and where posture breaks down. Since the lab is small, it’s not going to ingest massive volumes of data.

If more resources are needed temporarily, Wazuh can be shut off. That’s prioritization, not a bad homelab. Learning how to allocate limited resources is part of the lesson.

CPU was never the problem. Even with multiple VMs running, the Mac mini never felt CPU-bound. Memory was the real constraint, which is exactly the kind of constraint people should learn to reason about.

Minimum requirements are written for “bare-minimum specs for this thing to work like we intended”. Learning labs rarely look like that, and stability can sometimes be sacrificed to open up more learning.

Where the Raspberry Pi Trap Shows Up

This is where the Pi comparison becomes unavoidable.

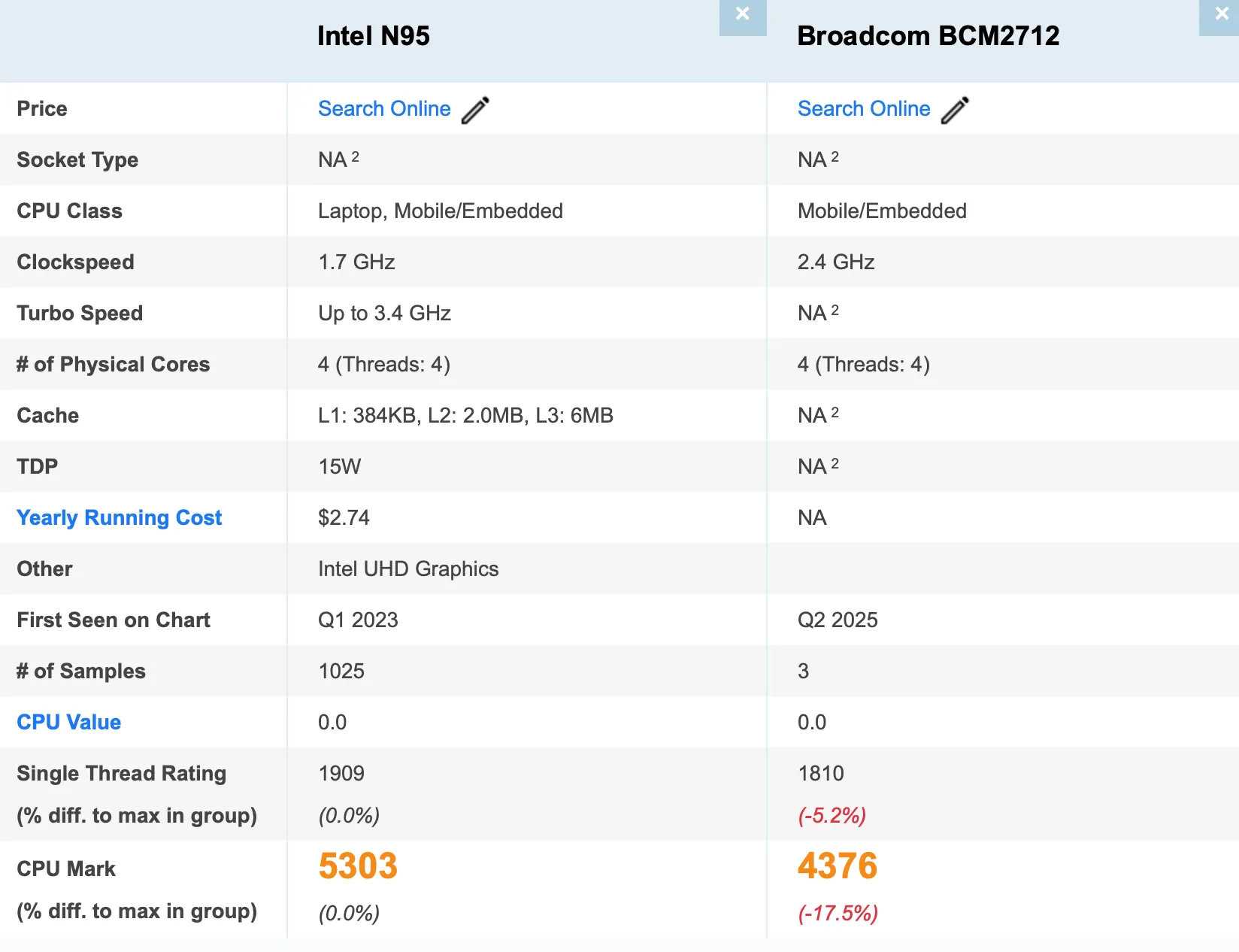

Raspberry Pis are excellent at what they are designed for. They are not great general-purpose learning platforms for infrastructure. Memory can be tight. SD card storage is annoying. Virtualization options are limited. Most production style tooling and documentation often assume x86.

To compensate, people add complexity via external storage, custom images, and workarounds. Suddenly the lab is harder to operate than the systems it’s meant to teach.

Old x86 hardware, on the other hand, brings boring advantages that actually matter.

- Mature virtualization support

- Predictable storage behavior

- Broad OS compatibility

- More horsepower dollar-per-dollar

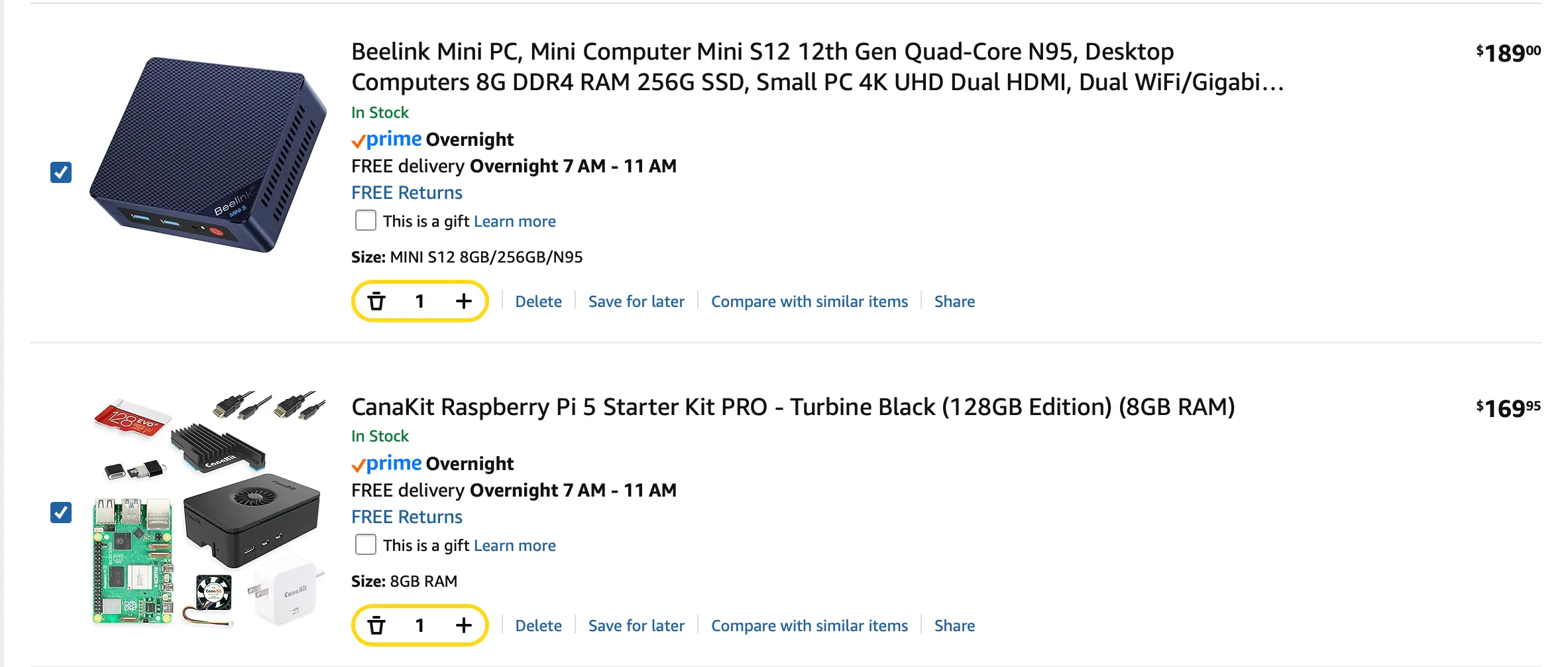

For the price of a Raspberry Pi, or often less when considering the SD card, power supply, and case, an old Mac mini or similar x86 box gives you more room to learn. More flexibility. Fewer artificial constraints.

This is the Raspberry Pi trap.

You need to spend more than the base cost of the board to get it to a working state, and it’s still not any more performant.

This Mac mini smokes the pi in most aspects of homelabbing, outside of being bigger.

Yes, I do Own and Use Raspberry Pis

Raspberry Pis still make sense for ARM experimentation, embedded projects, and lightweight workloads. They are great tools when used for the right problems.

The issue is treating them as the default answer for people who want to learn systems administration, blue team fundamentals, or real infrastructure concepts. Some common “good” Pi workloads I agree with are things like DNS or Home Assistant, which while under the homelab umbrella normally during conversations, are two services i’d prefer to be on their own low power device so when the main “server” (or macmini in this case) needs to update the OS, the rest of my family or network doesn’t start to fall apart.

The trap isn’t choosing a Raspberry Pi for your homelab.

The trap is feeling like you need special hardware before you can start.

OK, So Now What?

Most people don’t need better hardware. They need fewer distractions.

This Mac mini is not impressive. At 4 cores, 8 GB of RAM, and 512 GB of storage, it’s about as forgettable as most machines. That’s the point.

You can learn Active Directory, domain joins, logging, monitoring, virtualization, and Linux services on hardware that costs less than a Raspberry Pi. You do not need a powerful PC. You do not need new gear. You do not need a shopping list.

Most homelabs do not fail because the hardware is too weak.

They fail because complexity shows up before understanding does.

Boring hardware running real systems is more than enough to get started, and in many cases you’ll end up learning more.

Thanks for stopping by, stay caffeinated. ☕️

Keep exploring

Find more builds like this

Follow related tags or subscribe via RSS so the next lab experiment lands in your reader automatically.